The start of the affair: Young Tommy

Thomas Edward Godwin, known to friends and family simply as ‘Tommy’, was born in Fenton, Stoke-on-Trent on the 5th June 1912. At the time children grew-up quickly, were often raised in hardship and were expected to work from an early age. Tommy, no exception, took a job as a delivery boy aged twelve, which helped him to pull his weight and share the burden of providing for a family of twelve.

A requisite (and most likely to young Tommy a perk) of the job, Tommy was equipped with a heavy bike with which to complete his daily deliveries on behalf of the owner of a general store, newsagents and butchers. Tommy enjoyed riding the bike as part of his rounds, and an interest in cycling had sparked to life.

Who ate all the pies?

Not Tommy – he became a lifelong vegetarian after a brief stint working at a Burslem pie-makers. What an advert for vegetarianism he could be today!

A few years later, the then fourteen-year old Tommy would be inspired by an advert asking for participants in a local 25-mile time trial.

Legend has it that Tommy hacked off the heavy steel delivery basket from the front of his bike, and kitted out with both borrowed shoes and wheels proceeded to steam around the course in a winning time of one hour and five minutes.

Still at a tender age, the initial spark had already exploded into a full blown love affair with cycling.

Early success: Rising to the greatest challenge

Tommy’s ability was soon noticed, and in turn he joined the ‘Potteries Clarion Cycling Club’, the ‘Potteries Cycling Club’ and eventually the ‘Rickmansworth Cycling Club’ after relocating from Staffordshire to North-West London in order to find work.

Throughout this period, Tommy would rack-up a titanic assortment of medals, trophies and awards. Included in this 200-strong haul were awards for 25-mile and 50-mile time trials, team awards including both the ‘Bath Road’ and ‘Anfield Bicycle Club’s’ classic 100-mile events, as well as a pleasing 7th position finish in the 1933 ‘Best All-rounder Competition’.

Continued success was sought and found by Tommy, and late into the season of 1938 he remained one of the fastest 25 and 50 mile time-triallers in the country. Longer rides also proved no match for Tommy’s athleticism and he regularly competed in distance events up and down the country. The previous year, Tommy had first mooted a plan to challenge for the year record, a record recently won by the Australian pro-rider Oserick ‘Ossie’ Nicholson.

1939: Cometh the year, cometh the man

On the first day of the year, 1939, vegetarian, tee-totalling Tommy was fully prepared for the biggest year of his 26-year old life. He had only one New Year’s resolution in mind; to surpass the yearly mileage set by Nicholson in 1937, and return the record back to the UK.

Initial plans to mount a challenge on the year-record had become more substantial, and then boosted as Tommy sought and eventually gained the agreement of his employer to sponsor an attempt on the record. With sponsorship in place, Tommy was physically prepared, mentally prepared and fully equipped. His bike was fitted with a tamper-proof, sealed speedometer, and he had the neccessary means to document and verify the distances he would cover over the coming days, weeks and months.

At 5am, Tommy pushed off, and pedalled the first mile of a journey that ultimately would not end until a further 500 days, and 99,999 miles had been completed. By October 26th, Tommy had achieved what he had set out to do, and much, much more. The year record had not only been won, but with two months to spare, he had time enough to smash the previous record – and put it beyond reach for all others who would valiantly try, yet fail for many years to come.

After the dust had settled

It’s important not to forget that after Tommy had completed the year-record challenge on 31st December, that he didn’t just hang up his cycling shoes and take it easy in 1940. In fact just the opposite, Tommy would carry on riding huge mileages until mid-May.

Tommy, not entirely satisfied with the greatest year-ride of all time, wanted to push on further to gain a secondary record of the fastest completion of 100,000 miles! René Menzies, a previous holder of the year-record, had set the 100,000 mile target at an impressive 532 days.

By this time the restrictions imposed by an escalation of World War II were starting to make problems for Tommy. Besides the threat of a call-up to serve his country, Tommy was also hampered by dwindling food supplies (due to increasing rationing) and severe penalties for failing to abide to blackout restrictions.

Additional to this, Tommy had various sponsor and media commitments to attend; his 1939 ride had propelled him firmly into the limelight and he was a man very much in demand.

Nutrition bars and gel sachets weren’t an option for Tommy.

His diet was very simple: bread, milk, eggs, cheese – and even these became scarce as rationing began.

In the bleak midwinter

Indeed, the pressure increased further on Tommy and his quest to gain the 100,000 mile record. The UK had experienced a particularly harsh winter at the start of 1940, and the roads were treacherous with huge amounts of ice and snow covering the country.

Tommy had a terrible time in the freezing conditions, often skidding and falling from his bike. Damage to the bike, and also to himself, was all too common and simply had to be endured.

Eventually the winter broke and Tommy had the chance to pile on the miles. Tommy was back on track to beat Menzies’ record. On May 13th, 1940, Tommy rode into Paddington Recreation Ground Track; at long last, he had the finish line firmly in sight.

Watched by his sponsors, cycling friends and other dignitaries, Tommy rode the final mile of an epic, mammoth, legendary journey. Tommy had bagged yet another emphatic victory. Perhaps as an effort to help make the statisticians and sports writers jobs easier, he had covered the 100,000 miles in 500 days straight; a simple sum to work out that he had averaged 200 miles a day. Incredible.

The legend lives on

Tommy was called up to the RAF very soon after the end of his record-breaking ride. No chance to rest, or to reap the deserved publicity or financial rewards of his achievement, it was a tough break.

After the war, Tommy wanted only to return to cycling – and to race once again as an amateur. However, despite the best efforts of Tommy and his friends (several hundred whom had signed a petition on Tommy’s behalf), was unable to do so; the cycling governing bodies having ruled that once he had ridden as a professional he would be forever barred from amateur status.

Putting this huge disappointment behind him, Tommy concentrated his efforts on coaching and helping others. He became team trainer to the Stone Wheelers and was a huge supporter of the club throughout his life.

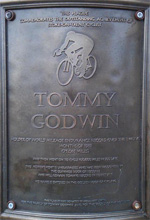

In 1975, Tommy aged 63, died while returning home from a ride with friends to Tutbury Castle. It seems fitting that Tommy’s last day on earth would be doing what he had loved doing all his life: riding a bike. In 2005, a plaque was unveiled at Fenton Manor Sports Centre, in order to pay tribute to the life and achievements of a much-loved and much-respected man.

Plaque reads as follows:

“This plaque commemorates the outstanding achievement of Stoke-on-Trent cyclist Tommy Godwin. Holder of the world mileage endurance record over the twelve months of 1939 (75,065 miles) and then went on to cycle 100,000 miles in 500 days.

This achievement is unsurpassed and has been recognised by The Guinness Book Of Records and will remain Tommy’s record in perpetuity. His name is also entered in The Golden Book of Cycling.”